Michael Shorstein’s inch-square classified ad appears everyday in the same spot, underneath the notices of lost pets, above the personals. “ADOPTIONS,” it says in capital letters, in between two hearts. “Many loving families.”

That promise brought Crystal Brown to Shorstein’s office three years ago. The Jacksonville woman was pregnant with her fifth child and abandoned by the father, a man who was not her long-estranged husband. Alone with her four other children, she felt it wasn’t right to bring another child into a broken home. She wanted something more for her baby boy than she was able to give her other children.

“I just wanted a family for him,” she said. “I wanted a mother and father in the home.”

Shorstein helped her find one. The Jacksonville lawyer has practiced adoption law since starting his own practice in 1991, exclusively for the past five years, and has focused just on birth mothers the past four.

He’s become not only a well-known voice speaking out for change in strict adoption laws, often lobbying legislators in Tallahassee, but also an important part of the lives of many parents either giving children up for adoption or looking to adopt.

Hitting Home

Many mothers wanting to put their babies up for adoption first turn to the phone book and go through the ads for adoption professionals like him, said Michael Shorstein, who advertises all over the country.

Both state law and the protocol of the agency or lawyer can vary widely. For instance, Florida is middle of the road as far as how much of the birth mother’s living and medical expenses the adoptive parents can pay for, Shorstein said. Some states allow them to pay for nothing, others for more.

The birth mother’s choice, then, is based on how much expense she will have and how much can be paid for, how involved she can be in the process of choosing adoptive parents, how comfortable she feels talking with the adoption professional on the phone, etc.

Shorstein allowed Brown to call him at home with problems. Learning that her children were balking at the idea of giving up a sibling, he brought them into his office to talk.

“He made us feel welcome,” she said. “There were days I was just an emotional basket case. He was always available to me.”

There is perhaps an unlikely rapport established again and again between these pregnant women from so many different walks of life and Shorstein, a lawyer from a family of lawyers – his uncle, Harry Shorstein, is state attorney.

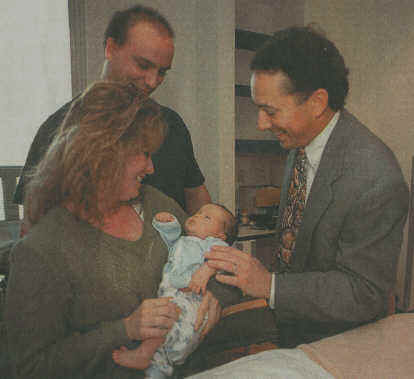

PHOTO – Don Burk/staff

Michael Shorstein (center) has helped Oklahoma couple Larry and Tammy Clifft place two children for adoption.

Michael Shorstein (center) has helped Oklahoma couple Larry and Tammy Clifft place two children for adoption.

A Gift

Or perhaps that rapport is not so unlikely. The happiness of Shorstein’s own home is evident in the photographs of his wife and two children, a 13-year-old-son and 10-year-old-daughter, that sit all over his office, a second floor room of an elegant old house in downtown Jacksonville.

“Michael is a good father and he enjoys being a father,” said Kathleen Stevens, adoption director of First Coast Adoption Professionals, the agency with which Shorstein works almost exclusively. “Because of that, he understands the gift they are helping the adoptive parents receive.”

In fatherhood, he had a good example, he said. Growing up in Jacksonville with two brothers, Shorstein’s goal in life was to follow in the footsteps of his dad, a lawyer and accountant.

“I always wanted to be like my father,” Shorstein said. “I loved growing up and had a great home, and I wanted a home like my father and mother’s.”

So like his dad, he earned his undergraduate degree in accounting, working in that field a while before getting his law degree from Florida State University in 1985. Shorstein practiced sports law for three years, then mostly criminal law for a few years in his uncle’s firm, until Harry Shorstein became state attorney. After a short stint in another firm, he started his own practice with attorney Brian Kelly and stumbled on adoption law almost by accident.

Friends asked him to facilitate an adoption for them. During research for the case, he found a niche he thought needed filling and a job he could feel passionate about.

“It was a perfect fit,” he said. “To facilitate that gift. You were the one who helped create that family. It was an extraordinary feeling.”

State Of Adoption

In his State of the Union address last week, President Clinton addressed an upsurge in adoption:

“…Our economic revolution has been matched by a revival of the American spirit: crime down by 20 percent, to its lowest level in 25 years; teen births down seven years in a row; adoptions up by 30 percent; welfare rolls cut in half to their lowest levels in 30 years.”

- According to the National Council for Adoption in Washington, approximately 54,500 unrelated (baby and adoptive parent were not blood relatives) domestic adoptions took place in the United States in 1996, the last year for which figures were available.

- Jacksonville attorney Michael Shorstein said that in his experience, the incidence of birth mothers changing their minds at the last minute – after the adoptive parents have already paid for their expenses – is extremely rare.

Likewise, the incidence of adoptive parents deciding at the last minute not to adopt the baby with whom they have been matched, perhaps for unforeseen medical reasons, is extremely rare.

– Colleen Steffen/staff

The Process

Before the 1980’s, almost all adoptions were closed. The birth mother and the adoptive parents never met and records were permanently sealed. But now, many people – all of Shorstein’s clients – prefer open adoptions in which the birth mother gets to select the family that will adopt her child.

Shorstein goes through the entire process nearly 100 times a year. First, he is contacted by a pregnant woman interested in giving her baby up for adoption. Although commonly low-income and in their early 20s, without any emotional or financial support from the father of their child, birth mothers coming to Shorstein for help cannot be so easily labeled. He has helped women as young as 12 and as old as 44, many educated and from affluent families, more and more of them married with children at home.

Shorstein will have two or three meetings with the mother and, if possible, the father. These are informational conversations, their tone set by Shorstein’s own informal, conversational manner. Younger-looking than his 42 years, usually without a jacket and tie unless he has been in court that day, Shorstein quickly puts strangers at ease with an outgoing, almost overwhelmingly friendly personality.

But he is listening carefully, and the information he learns about the birth mother and her preferences in an adoptive family he sends to First Coast Adoption Professionals, which currently has a waiting list of more than 100 families wanting to adopt. They have also made known their preferences in a birth mother, and how much they can afford to pay, not only for Shorstein’s and the agency’s combined fee but also for the birth mother’s medical and living expenses. First Coast then sends Shorstein five or six profiles of prospective families that seem to match the birth mother’s wishes. [Subsequent to this article, in 2003, Shorstein established his own waiting list of families wanting to adopt.]

Typically, the birth mother will pick two or three of these that strike a cord with her and then talk with the couple on the phone, or meet them in person if they are nearby. There is no science to this choosing of her baby’s future family – just a gut instinct that Shorstein encourages each woman to listen to.

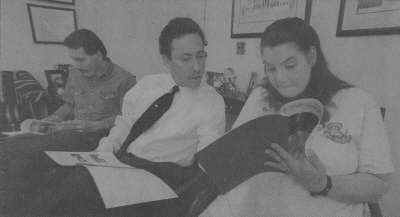

One recent afternoon, Shorstein helped Tammy and Larry Clifft, a married couple from Oklahoma, page through profiles of prospective parents in his office. They all looked at all the pictures of smiling couples, poured over the descriptions they had written about themselves. Some talked about years of struggle through infertility treatments, multiple miscarriages.

Michele Brown of Atlanta said this waiting to be chosen, waiting for your profile to touch someone’s heart, is the worst part of the adoption process.

“You’ve already gone through a lot of infertility problems, and waiting, and shots, and surgeries, and disappointment,” she said. “It’s very physically and emotionally and financially draining.”

Yet, while Shorstein was in the process of helping them adopt their now 6-month-old daughter, she and her husband felt they had put themselves in good hands.

“Now we have this baby,” Brown said, “and she’s beautiful inside and out.”

New Family

Colleague Amy Hickman, an adoption and family law attorney in Boynton Beach, described Shorstein as experienced, a person of integrity.

“He’s very pleasant. He’s very easy to work with,” she said. “You know he is going to do a quality job.”

“He really has a very good reputation, which is evident by the number of people who want to do work with him,” agreed Laurie Goldheim, an adoption lawyer in New York. “Michael has a unique, wonderful way with the birth mothers. It’s his ability to relate to the women and their situations.”

The Cliffts paid Shorstein perhaps the highest compliment by seeking his help not once but twice. Both Tammy and Larry Clifft have two children by previous marriages and feel incapable of caring for another. Religious conviction and past experience – Tammy Clifft was herself an adopted child – prevented them from seeking an abortion a few years ago when they found themselves expecting.

Shorstein helped them place the baby with a family with whom they still keep in touch. Now pregnant again, paging through his stack of profiles hoping for a match as good as their first. That adoptive mother not only sends them photographs of the baby they gave up, but even stayed with Tammy through her labor and delivery.

“What was nice was when [the baby] was born, to see the smile on her [the adoptive mother’s] face,” Tammy said, her eyes growing moist. “That made it nice.”

Speaking Out

That sort of smooth transition is Shorstein’s goal. That’s why he feels compelled sometimes to lobby against proposed laws he feels will make the adoption process more difficult and complicated.

Last year, Shorstein met fellow adoption colleagues in Tallahassee seven or eight times, speaking before legislative committees and lawmakers against proposals to place greater limits in the expenses adoptive parents are allowed to pay for example.

Requiring more documentation every time adoption professionals talk to birth mothers or adoptive parents, and barring out-of-state couples from adopting in-state babies were two other proposals he was against.

Shorstein has no such trips to Tallahassee planned for this year, but he is always prepared to go when an adoption issue arises, even though the political issues are not one he relishes.

Some facets of his personality he tends to keep to himself, details hinted at by the pictures in his office if nothing else – his attachment to his faith and his family. It takes a little prodding to learn he is president-elect of Jacksonville Jewish Center, in which he grew up. And it is his wife, Robin, not him, who tells how he has rarely missed any of his children’s school or sports programs, or how devotedly he visited his sick mother before she died a few years ago.

The Reward

One recent afternoon, a couple Donna and Jerry – who asked that their last name not be used – came to Baptist Medical Center to take home their new adopted son. They looked like two people who had just fallen in love, unable to take their eyes off the baby, unable to stop smiling, on the edge of tears.

At that amazing moment, Shorstein could have been mistaken for a proud uncle, or even the father, his booming voice, cracking jokes, heard up and down the hall. Often, he takes pictures to mark these occasions, snapshots of the new parents, of him holding the baby.

“They’re identical to the pictures of him holding his own children,” said his wife, Robin, who thinks she knows why he was drawn to this work.

“In law, there are so many things that are sad and depressing and difficult,” she said. With this, “everybody wins, the birth mother, the adoptive parents and the child.”

An appointment in court finalizes what Shorstein has helped make possible; a new family, a woman with renewed opportunity. But that is not usually the last he hears from the players in these small dramas, who often feel compelled to check back with him.

Those notes and phone calls and pictures are surely the best reason of all for Shorstein.

“It’s the only thing I’ve ever done,” he said, “I’ve ever found incredibly rewarding.”